How The Penguin Update Affected Link Building In 2012

Google’s “Penguin” algorithm update in 2012 marked a turning point for SEO professionals focused on link building. At the time, link building was a cornerstone of search engine optimization, but Penguin fundamentally changed how Google evaluated links and, in turn, how SEOs approached getting backlinks.

This post provides a historical overview of link building practices before Penguin, examines the Penguin update’s goals and immediate impact, and explores how it forced the SEO industry to adapt both in the short term and long term.

Along the way, we’ll include insights from Google spokespeople and industry experts, relevant case studies, and the nuanced debates that Penguin sparked in the SEO community. The emphasis is on how Penguin drove changes in link building strategies, rather than simply highlighting risks, though we will also cover potential downsides that arose.

Historical overview of link building practices before Penguin

In the early 2000s up to the early 2010s, link building often prioritized sheer quantity over quality.

In the pre-Penguin era of search, many SEO practitioners treated link building as a numbers game.

The prevailing wisdom was that “a link was a link” – almost any backlink could help improve rankings, even if it came from a low-quality or spammy site, because Google’s algorithms weren’t very effective at distinguishing link quality.

This led to a flourishing of “easy” link-building tactics that were technically against Google’s guidelines but still worked wonders for boosting PageRank and search rankings.

Common link building techniques before 2012 included submitting sites to countless web directories, syndicating articles en masse to article directories, dropping links in blog comments and forum signatures, exchanging links with other webmasters, and even outright purchasing links on high PageRank sites.

Many of these methods were highly scalable – one could pay for “500 directory links” or “1,000 article submissions” as part of an SEO package and expect improved rankings.

Because these tactics consistently delivered results and carried relatively little immediate risk, they were widely adopted. Not just shady operators, but even well-known “white hat” SEO agencies engaged in large-scale directory submissions, article marketing, and similar tactics in those days.

The rationale was simple: these techniques “worked and posed little risk” at the time. Google’s guidelines explicitly forbade many link schemes, but enforcement was limited – mostly manual penalties reserved for egregious cases.

For the average site, as long as you mixed in a few higher-quality links, you could get away with a lot of manipulative links without consequence.

By the late 2000s, the web was littered with low-quality content whose sole purpose was to provide a backlink. Entire link networks and link farms existed solely to funnel PageRank.

Because Google’s ranking algorithm placed heavy weight on backlinks, the SEO environment became a bit of a “wild west”. This is illustrated by how certain sites with thin content could rank well just by accumulating massive numbers of inbound links. Google occasionally released minor updates or manual crackdowns to combat link spam (for example, the J.C. Penney link scandal in 2011 led to a manual penalty), but there was no sweeping algorithmic solution for link spam. As one retrospective noted, it wasn’t until 2012 that SEO techniques for link building truly came under serious fire from Google.

In essence, prior to Penguin, the path to higher rankings was often “get as many links as possible, wherever you can”, and the quality or relevance of those links was a secondary concern.

The 2012 Penguin update and its key targets

In April 2012, Google launched a major algorithm change initially dubbed the “webspam algorithm update,” which the industry soon christened Penguin.

This update was explicitly aimed at cracking down on unscrupulous link tactics and other forms of webspam that violated Google’s quality guidelines. Google announced that this change would

“decrease rankings for sites that [Google] believe[s] are violating [its] existing quality guidelines”

specifically calling out aggressive webspam tactics. Unlike Google’s prior “Panda” update (2011) which targeted low-quality on-page content, the Penguin update focused on off-page factors – chiefly the backlink profile of websites.

One of Penguin’s immediate impacts was its broad scope: it was estimated to affect over 3% of search queries – a very large swath of searches – upon its initial rollout.

To put this in perspective, millions of sites saw changes in their rankings overnight. Google’s own post on the update (cross-posted on the Inside Search blog and the Webmaster Central blog) advised webmasters to focus on high-quality content and “white hat” SEO going forward.

While Google didn’t list specific tactics in that announcement, it was clear that manipulative link building practices were a prime target. Subsequent analysis and communications from Google confirmed that Penguin primarily targeted “link schemes” – an umbrella term covering paid links, link exchanges, link farms, blog networks, or any other unnatural link building intended to game rankings.

In Google’s eyes, these black-hat link tactics violated the principle that links should be editorial votes of confidence. Penguin also looked at other spam factors (some reports noted it affected keyword stuffing on pages to a degree), but inbound links were the main focus.

Critically, Penguin was an algorithmic penalty (or demotion) rather than a manual action. Google’s Matt Cutts (head of webspam at the time) explained that Penguin

“does demote [certain] web results, but it’s an algorithmic change, not a [manual] penalty.”

This meant sites hit by Penguin wouldn’t receive a specific warning or notice; their rankings would drop as a result of the algorithm detecting an unnatural link profile. Webmasters could not simply file a reconsideration request to have a Penguin hit lifted (at least not in 2012); they generally had to remove or disavow bad links and then wait for the algorithm to refresh to see recovery.

The types of links and patterns that Penguin targeted became evident through industry analysis. Websites that had over-optimized anchor text – for example, if 70% of your backlinks used the exact same money keyword – were highly vulnerable.

One industry study noted that sites hit by Penguin often had “exact match anchor text on head terms for more than 60% of their inbound links”, an astonishingly unnatural profile. Likewise, sites with a huge proportion of links coming from obviously spammy sources (like footer links on hundreds of unrelated sites, or dozens of blog comments with commercial anchor text) were likely to get caught.

Google essentially turned the webspam dial up: tactics that had previously been merely disregarded or devalued could now actively cause harm by triggering a ranking demotion.

One webmaster shared a chart depicting a Penguin-related ranking collapse. The table shows a site’s Google rankings (middle column, highlighted in blue) for various keywords dropping dramatically (red arrows indicate rank drops) after Penguin, while the same site’s Yahoo and Bing rankings remained relatively stableseroundtable.com. This stark contrast illustrates how Google’s Penguin algorithm specifically penalized the site’s search visibility on Google – the site lost dozens of positions for many keywords on Google (red values), even as it held steady or improved on Yahoo (green values) and Bing. Such examples made it clear that Penguin was the cause of these ranking crashes, not a general market fluctuation or seasonality.

The Penguin update quickly earned a fearsome reputation among webmasters. Within weeks, surveys showed a large portion of SEO professionals were affected. In one poll of about a thousand SEOs conducted shortly after Penguin’s launch, almost 65% reported that one or more of their sites had been negatively impacted.

This made Penguin arguably more feared than Panda; a separate survey found 65% of marketers said they were hurt by Penguin compared to 40% by the Panda content update. Barry Schwartz of Search Engine Roundtable described “tremendous casualties” from Penguin and advised sites that believed they were wrongly hit to submit their case to Google for review. Google even provided a special feedback form for Penguin issues, essentially acknowledging that some innocents might have been caught in the dragnet.

From Google’s perspective, Penguin was a necessary step to improve search quality. Cutts noted that Panda had addressed spammy on-site content, but “there was still a lot of spam” in the form of manipulative links, and Penguin was “designed to tackle that” gap.

The strategic goal was to reduce the effectiveness of black-hat link-building strategies and reward those sites earning natural, relevant links. In Cutts’s words, Google wanted to ensure that “natural, authoritative, and relevant links” rewarded the websites they point to, while devaluing “manipulative and spammy links.” It was a rebalancing of the link signal to favor quality over quantity.

How Penguin changed link building: immediate industry reactions

Penguin’s rollout in 2012 sent shockwaves through the SEO industry. Sites that had thrived on aggressive link building saw overnight losses in traffic and rankings, prompting an urgent re-evaluation of tactics. In the short term, the priority for many was damage control: identifying and addressing bad links as quickly as possible.

One of the first major shifts was the rise of the “link audit.” Webmasters scrambled to review their backlink profiles – often for the first time ever – to figure out if they had harmful links that might have caused a Penguin hit. This was a daunting task: some sites had amassed tens of thousands of links across various link-building campaigns over the years.

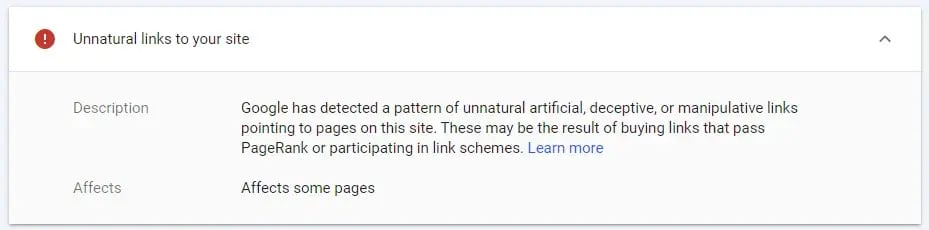

SEO forums in mid-2012 were filled with discussions on how to tell a bad link from a good one, and which links to try to remove. Google itself exacerbated this frenzy by sending out an unprecedented number of “Unnatural links to your site” warnings via Google Webmaster Tools (now Search Console) around the same time.

Example of a Google Search Console “Unnatural links” warning. Around the time of the Penguin rollout, Google sent out a surge of these alerts to webmasters. The notification indicates Google has detected a pattern of “unnatural, artificial, deceptive, or manipulative links” pointing to the site – for example, links that may be the result of buying links or participating in link schemes. Such warnings, combined with Penguin’s algorithmic penalties, spurred many site owners to urgently clean up their backlink profiles (removing or disavowing “toxic” links) in order to restore or protect their Google rankings.

Because of Penguin’s immediate and automatic nature, webmasters undertook the tedious process of removing bad links. This often meant contacting webmasters of spammy directories, article sites, or blogs and asking for links to be taken down. SEO agencies were suddenly inundated with requests to “clean up” backlinks.

In fact, a whole sub-industry of link removal services emerged. Google soon realized webmasters needed better tools to help with this process – by October 2012, Google rolled out the Disavow Links tool, which allowed site owners to submit a list of bad links for Google to ignore. Matt Cutts indicated in June 2012 that Google was “talking about” enabling a disavow capability, acknowledging the community’s concerns about unwanted links and negative SEO. The disavow tool became a crucial recovery mechanism for Penguin-hit sites, though Google advised it be used with caution.

For many SEOs, Penguin also meant a fundamental change in philosophy from “building” links to “earning” links. Tactics that were once staples of SEO had to be abandoned or drastically curtailed.

For instance, article marketing, where one would syndicate slightly tweaked articles with optimized anchor text backlinks across dozens of sites, was now a red flag – Google explicitly mentioned article marketing as problematic after Penguin.

Directory link-building, once a cheap and easy link source, became largely obsolete overnight (except for a handful of high-quality, niche directories).

Comment spamming on blogs and forums, which many low-end SEO services had automated, was now a sure way to get in trouble – Google’s algorithm (and manual webspam team) could easily identify patterns of spammy comment links.

Site-wide footer or sidebar links (e.g., a link in the footer of 500 different websites all pointing to your site with the same anchor text) also came under scrutiny; those links, once valued for passing lots of PageRank site-wide, started to look incredibly unnatural post-Penguin.

The immediate guidance from experts was to stop any “easy link” tactics and focus on quality instead. Jim Boykin, a well-known link builder, spoke at SES San Francisco 2012 about “Penguin-friendly” link strategies.

He cautioned against things like homepage links on random sites, sitewide links, mass article syndication, forum signature links, and low-quality blog comments – essentially, the very tactics that had been SEO bread and butter a year earlier. Boykin’s advice (backed by data from his clients) was to be vigilant and weed out “suspicious links” that could trigger penalties, while concentrating on acquiring links from more relevant and authoritative sources.

Another immediate change was in anchor text strategy. SEOs quickly learned to diversify the anchor text in their backlink profiles. Before Penguin, it was common practice to try to have the majority of links include the exact keyword you wanted to rank for – it was almost a maxim of SEO that more exact-match anchors = higher rankings. Penguin turned that upside down.

Marketers began emphasizing branded anchors (like “ExampleCompany.com” or “Example Company”) and generic anchors (“click here”, “this article”) in their link building efforts. The goal was to mimic natural link patterns where only a minority of links would use a commercial keyword.

For sites trying to recover from Penguin, reducing the percentage of exact-match anchors was often step one. In one case study, a website that had over 65% exact-match keyword anchors (pre-Penguin) dropped that ratio into the teens post-cleanup – and saw improvement in rankings once Penguin reran, suggesting that diluting anchor text helped escape the penalty.

Perhaps the most important immediate impact of Penguin was a mindset shift: quality over quantity. This might sound cliché now, but in 2012 it represented a sea change for many SEO practitioners. Instead of asking “How many links can we build this month?”, the question became “What kind of links should we build that won’t get us in trouble and will actually help long-term?”.

Earning one link from a highly respected, relevant website became far more valuable (and safer) than getting 100 links from low-quality sites. This mindset shift was reinforced by messages from Google and thought leaders. Google’s Cutts repeatedly said there are

“no shortcuts”

– great content and a great user experience are the safe path forward. At the same time, industry voices like Danny Sullivan hammered home that search engines don’t want artificial link manipulation: Sullivan famously quipped at an SMX conference, “search engines do not want you to build links – they want your content to earn links.” This quote, in mid-2012, perfectly encapsulated the post-Penguin ethos that quickly took hold.

SEO agencies and consultants responded by overhauling their services. Many rebranded their link building offerings as “content marketing” or “digital PR.” The idea was to create link-worthy content (infographics, research studies, guest editorials, etc.) and promote it to attract links, rather than placing links yourself on dubious sites.

In the short run, this was a scramble – not everyone had the skills or resources to produce great content and do outreach, especially agencies that had been built on cheap scalable link tactics. Some businesses felt the pinch as they had to invest more heavily in content creation or accept a slower, more organic growth in links.

It’s worth noting that in the immediate aftermath, there was also panic and confusion. Some webmasters weren’t sure if their drop was due to Penguin or other factors. Google’s communication wasn’t perfect – for example, they sent out 700,000 unnatural link notices in spring 2012, but later clarified that “only a single-digit percent” of those were directly related to Penguin action.

In other words, many got warnings even if they weren’t being algorithmically penalized, which led to overreaction. Cutts had to clarify on his Google+ that “if you got a warning, don’t panic… it’s not necessarily something you need to worry about”. This mixed messaging meant some site owners went overboard disavowing or removing links that weren’t actually hurting them. The savvier SEOs counseled a balanced approach: address clearly spammy links, but don’t throw the baby out with the bathwater by cutting off every link with keyword anchor text (since some might be legitimate).

Long-term industry adaptations and the new link building landscape

In the longer term, Penguin’s influence fundamentally reshaped how the SEO industry approached link building. The changes that began in 2012 set the tone for the next decade of off-page SEO strategies. After the initial triage and cleanup phase, SEOs evolved to thrive in the new reality where link quality, relevance, and authenticity are paramount.

One significant long-term adaptation was the focus on “earning” links through high-quality content and outreach rather than “building” links through manipulation. Content marketing became inseparable from link building. Companies poured resources into creating blog posts, guides, infographics, videos, and other assets that people would naturally want to link to.

The idea was to attract links organically by offering value. While “build it and they will link” doesn’t magically happen without promotion, this era saw a big uptick in outreach-based link building – PR-style efforts to pitch content to journalists, bloggers, and webmasters in hopes of getting a mention or link.

In short, link building started to look more like traditional public relations and relationship-building.

Guest blogging

emerged in the early 2010s as a popular legitimate link-building technique, and Penguin accelerated that trend. Rather than posting spun articles to article farms (now a taboo practice), SEOs moved toward writing high-quality guest articles for real, respected blogs in their niche, with a contextual backlink to their site.

For a few years post-Penguin, guest blogging was widely viewed as a safe way to build links as long as the content was useful and not overtly advertorial. (It wasn’t until later, around 2014, that Google warned against spammy guest posting at scale, when that too started being abused.)

Online PR campaigns also flourished as a strategy. Brands would create linkable assets or conduct studies and then pitch them to news sites or industry publications. If successful, this could earn links from high-authority domains – the kind of links that not only would be Penguin-safe, but highly beneficial for rankings.

This approach stood in stark contrast to pre-Penguin link farming; it required creativity, newsworthiness, and genuine outreach effort.

Another lasting change was that SEOs became much more vigilant about their backlink profiles on an ongoing basis. It became routine to periodically audit new links to catch any spammy ones. The practice of disavowing links turned from a one-time recovery action to a regular preventive measure for some.

Particularly for sites in competitive niches (where competitors might try negative SEO), monitoring backlinks became as important as tracking keyword rankings. The industry also developed better tools for link analysis – companies like Ahrefs, Majestic, and Moz refined metrics (like Moz’s Spam Score or Majestic’s Trust Flow) to help identify potentially bad links. Google’s own Search Console improved its link reporting over time, giving site owners more transparency.

Penguin’s algorithm itself went through several updates in the years following 2012, and the SEO community kept a close eye on each iteration. Notably, Penguin 4.0 in 2016 was a game-changer in that Google made Penguin run in real-time as part of the core algorithm, and importantly, stopped Penguin from demoting sites outright.

Instead, by 2016 Penguin merely devalued bad links (ignored their credit) rather than applying a harsh penalty to the entire site. This was a welcomed change, effectively solving the long lag problem – sites could recover faster, and truly negative SEO became less of a threat because Google would simply not count spam links rather than punish the target.

However, these later developments don’t erase the fundamental paradigm shift that Penguin introduced in 2012: by then, the SEO world had already embraced a cleaner link building approach.

From a business perspective, Penguin weeded out a lot of low-quality SEO providers who couldn’t adapt. Agencies that had relied on churning out cheap links at scale had to either reinvent themselves or saw their clients leave. Conversely, agencies that focused on content, creativity, and genuine outreach began to dominate.

The notion of “Domain Authority” became more important than sheer link counts. Marketers aimed to get links that would improve their Domain Authority/Rating, rather than just increase the raw number of backlinks. This often meant targeting one link from a DA 80 site instead of 100 links from DA 10 sites, for example.

The conversation around link building also matured.

Whereas in 2011 an SEO might brag about building 1,000 links in a month, by 2013 the bragging rights shifted to the caliber of links earned – e.g., “we got a mention on The New York Times or a link from .edu sites relevant to our industry.” Link building in the post-Penguin world had more in common with business development and content strategy than with automated submissions. It also meant SEO had to collaborate more with other teams: content writers, designers, PR professionals, social media – all became partners in earning links, reflecting a more holistic approach.

Penguin drove home that the user is king. If a link didn’t provide some value to a human user (say, as a relevant citation or a useful resource), it was likely not the kind of link Google wanted to count. This principle started guiding link building efforts. SEOs began to ask: “If Google didn’t exist, would I still want this link for referral traffic or visibility?” If the answer was no, it was probably not worth pursuing. This mindset greatly reduced the tendency to do spammy things just for SEO’s sake.

Insights from experts and Google spokespersons

Throughout Penguin’s rollout and the years after, Google representatives and SEO experts frequently weighed in with advice, clarifications, and opinions, which helped shape industry understanding of the update.

Matt Cutts, as Google’s head of webspam in 2012, was the primary spokesperson on Penguin. In the months after launch, Cutts spoke at conferences and gave interviews to address the myriad questions SEOs had. One key point he emphasized is that Penguin was not a one-time “penalty” but part of an evolving algorithmic approach.

He noted that both Panda and Penguin would see continued updates and that Google’s goal was to refine these algorithms to better catch spam while avoiding false positives. Cutts explicitly said, “SEO is going to get more difficult” going forward, suggesting that Google would continue raising the bar and closing loopholes exploited by black-hat SEOs.

On the topic of negative SEO, which quickly became a concern (since Penguin made it theoretically possible to harm a competitor by pointing bad links at them), Cutts and Google initially tried to allay fears. Google’s messaging shifted from earlier statements that “nothing a competitor can do can hurt your rankings” (a claim that pre-dated Penguin) to a more measured line that negative SEO is possible but difficult.

Cutts acknowledged that Google had updated its help documentation to reflect that negative SEO is “not impossible, but it is difficult” to pull off successfully. He also said Google’s teams work hard to prevent it. The introduction of the Disavow Tool was partly to give site owners peace of mind – a way to counteract any malicious links.

In practice, confirmed cases of successful negative SEO have been relatively rare, but the fear of it pushed many to be proactive about disavowing suspicious links.

Google’s advice through this period consistently underscored quality and relevance. Whenever asked how to do link building safely, Cutts would point back to the Google Webmaster Guidelines, which essentially say: earn links naturally, don’t participate in link schemes, and focus on content. In one memorable exchange, Cutts warned about buying links by saying, “when you buy links, you might think you’re being careful… but you may be getting into business with someone who’s not as careful. As we build new tools, [link buying] becomes a higher-risk endeavor.”

This was a direct signal that Google was actively developing technology (like Penguin) to detect paid or otherwise manipulative links, and that what worked yesterday might not work tomorrow. Many SEOs took this to heart and either stopped buying links altogether or became extremely cautious about any kind of paid link (e.g., insisting on nofollow tags for any sponsored placement, as per Google’s guidelines).

SEO industry experts, on the other hand, offered a mix of support and skepticism regarding Penguin. Rand Fishkin of Moz, for example, was an advocate for “earning over acquiring” links even before Penguin, and after the update he doubled down on advising SEOs to build “linkable assets” and invest in their brand to attract links.

Eric Ward (known as “Link Moses”), a pioneer of link building, applauded the update, arguing that it validated the approach he’d long preached: only seek links you actually deserve. Ward and others provided guidance on doing “risk assessment” of links – effectively, teaching SEOs to think like Google and identify which of their own tactics might look manipulative.

Not all experts agreed on everything, of course. There was some debate about specifics like exact-match anchor text. Jim Boykin’s SES presentation suggested that, in his data, a few exact-match anchor text links could still boost rankings significantly (he cited a client case where two exact “money keyword” links moved a page from #85 to #5 in Google).

This seemed to contradict the general consensus that exact-match anchors were a Penguin hazard. Boykin’s caveat was that his results were anecdotal and “contrary to other industry data”, so he advised being careful and monitoring if using targeted anchors at all. His stance highlighted a nuance: it wasn’t that keyword anchors suddenly didn’t work – they did, which is why Google targeted them – it’s that the overuse or unnatural patterns of them would trip the filter. So the community had to find a balance between optimizing anchors and keeping them natural.

Another insight from Boykin’s talk was the emphasis on content and “building your brand and community.” He famously said, “Good marketers do good things and get relevant traffic and links. Great marketers build brands and communities…” meaning the focus should be on broader marketing that naturally yields links, rather than chasing links in isolation. This sentiment was echoed widely post-Penguin: a strong brand (with lots of branded searches and mentions) and a loyal community can help generate organic links, which are exactly what Google wants to count.

Industry publications like Search Engine Land, Search Engine Journal, and Moz consistently put out guides and articles after Penguin to help people adapt. Titles like

“Link Building is Not Dead, It’s Just Different”

became common. Experts in those articles asserted that links remained as important as ever for ranking – Google still used links heavily in its algorithm – but the definition of a “good” link had changed. One Search Engine Land piece insisted “links are just as important as they were a few years ago”, clarifying that it’s the manipulative link building that was dead, not the pursuit of links itself.

Similarly, marketing guru Neil Patel quipped,

“It’s no secret that link building is critical to success when it comes to ranking organically.”

– a reminder that you couldn’t simply stop caring about links because of Penguin; you just had to earn them the right way.

The long-term expert consensus that emerged was: Penguin made SEO harder but ultimately cleaner. The update was painful for those who relied on spam, but it pushed the industry to align more with Google’s mission of rewarding relevancy and quality. Case studies were shared of sites that survived Penguin unscathed – invariably, these were sites that had focused on content and had a naturally diversified link profile.

For example, some SEOs pointed out that big brands generally weren’t hit (unless they had blatantly been buying links) because their link profiles tended to have lots of branded anchors and genuine mentions. This reinforced the idea of building a brand as a defensive SEO strategy.

Case studies: link building success in the post-Penguin era

B2B SaaS

While Penguin punished sites with manipulative backlinks, it also indirectly highlighted the success of those who took a “white hat” approach to link building. In the years since 2012, numerous case studies have demonstrated that focusing on quality content and legitimate link outreach not only avoids penalties but can deliver impressive SEO results. Here, we summarize a few relevant case studies that show what link building looked like after Penguin, and how sites thrived by embracing the new rules of the game.

One case study from The Backlink Company highlights a B2B SaaS startup that had virtually no online presence – a Domain Rating of only 4 and about 30 organic visitors per month. They engaged in an SEO and link building campaign that strictly followed quality guidelines: comprehensive content creation combined with “strategic link building” via outreach and guest posting on relevant sites.

Over a period of a few months, 180ops saw a dramatic turnaround. Organic traffic jumped from roughly 30 visitors to 1,700 visitors per month, and their Ahrefs Domain Rating climbed from 4 to 40. This 13x increase in traffic and massive authority growth were achieved with no risky link schemes, just steady acquisition of high-quality backlinks. It underscores that in a post-Penguin world, you can still increase your backlink count and authority significantly – as long as the links are earned on merit. The case study notes that consistent, contextual links from reputable publications were key, and it maintained a “consistent pace of link acquisition for sustainable growth”. Notably, this approach aligned perfectly with Penguin’s philosophy: rather than 1,000 spammy links, they built a portfolio of fewer, high-value links that Google rewarded.

B2B e-commerce

In another example, a Nordic B2B e-commerce company lost traffic over time and needed to regain visibility. The case study reports that by focusing on link building for just a few weeks – specifically securing high-quality backlinks to boost the site’s authority – the company managed to double its organic traffic in 3 weeks.

Google search impressions for the site also tripled (a 200% increase), and the site’s Domain Rating improved from 25 to 33 in that short span. These results were achieved by adhering to best practices: the company already had strong content, and the link building campaign simply aimed to get that content the authority it deserved. The strategy emphasized obtaining links from niche-relevant websites and avoiding any tactics that might raise red flags.

Importantly, the SEO team educated the client on how high-quality links can be built without getting penalized by Google, underscoring the point that link building per se isn’t forbidden – only the spammy kind is. The case study also cites that over 60% of businesses outsource link building to specialized agencies or experts, reflecting how mainstream and above-board the practice of responsible link building has become in the post-Penguin era.

What these case studies share is a focus on relevance, authority, and a human-centered approach to link acquisition. The links that moved the needle came from websites that make sense for the given industry (for example, SaaS or e-commerce industry blogs, tech news sites, etc.), often via content that provided real value (like guest posts offering expert insights, or resources that earned editorial links).

By aligning their tactics with Google’s guidelines, these businesses not only avoided penalties but also achieved robust growth in rankings and traffic.

In essence, they proved that Penguin did not kill link building – it refined it. If anything, Penguin weeded out the low-quality noise, so when a site now invests in genuine link building, the results can be very rewarding because those high-quality links shine through.

Nuances and opposing viewpoints in the SEO community

The Penguin update, being as impactful as it was, naturally generated debate and differing viewpoints within the SEO community. Not everyone agreed on how to react, and there were discussions about fairness, effectiveness, and the broader implications of Google’s approach.

One major discussion was about the severity of Penguin’s punishments and the recovery process. Early Penguin versions (2012-2014) could be brutal – a site could lose nearly all its organic traffic overnight and stay down for months or even years if it didn’t manage to clean up in time for the next Penguin refresh.

Some SEOs felt this all-or-nothing approach was too harsh, especially for small businesses that may have unknowingly hired bad SEO firms. The opposing viewpoint from others (and Google’s implicit stance) was that “if you play with fire, you risk getting burned” – in other words, sites benefiting from spammy links shouldn’t be surprised when the rug is pulled out. The nuance here is that some sites truly didn’t know what their SEO agencies were doing.

For instance, a small business might have paid for SEO and been kept in the dark about a bunch of dodgy directory submissions, only to find itself penalized. This led to some resentment and claims that Penguin punished the wrong party (the business rather than the SEO agency). Google’s advice to such site owners was to take responsibility for all links to their site and clean up the bad ones regardless of how they got there, which was a tough pill for some.

The concept of negative SEO was perhaps the most contentious topic. Pre-Penguin, most SEOs didn’t worry that a competitor could harm their site with bad links – Google’s algorithms largely ignored what it deemed spammy, so worst case those links wouldn’t help, but they wouldn’t hurt either. Penguin changed that perception by actively penalizing spammy link profiles. Suddenly, forums lit up with people asking,

“Can my competitors point garbage links at my site to make me tank?”

Cases were discussed where people saw a burst of strange, spammy links to their site and then a ranking drop. Google continued to insist that true negative SEO was rare and difficult, and that they have protections in place.

Nonetheless, the fear of negative SEO prompted many webmasters to vigilantly disavow any suspicious links as a precaution. In the community, some argued this was unnecessary – if you hadn’t received a warning or seen a drop, Google was likely ignoring those spam links anyway, and over-disavowing could even remove some benign links that might help.

Others took a “better safe than sorry” approach, periodically pruning their backlink profile via disavow files. The debate highlighted a lack of transparency: only Google knew exactly which links it was counting or not, leaving SEOs to make educated guesses.

Over time, especially after Penguin 4.0 (which stopped penalizing and started ignoring bad links), the negative SEO concern has calmed down a bit. But to this day, the community still occasionally encounters puzzling situations that rekindle the debate (for example, a site getting thousands of spam links and no visible negative effect – was Google truly ignoring them, or was the site just strong enough to withstand it?).

Algorithmic action vs. manual action

Another nuance in the Penguin discussion was the differentiation between algorithmic action vs. manual action. Penguin was algorithmic, meaning no Google employee reviewed your site; it was purely data-driven.

However, Google still had (and has) manual penalties for links. In 2012, a site could be hit by Penguin and also receive an “Unnatural Links” manual penalty separately. This muddied analyses – webmasters sometimes weren’t sure if they were under Penguin’s algorithm or a manual action or both.

Google’s advice was: if you get a manual penalty (which comes with a message), you must file a reconsideration request after cleaning up. But for Penguin, reconsideration requests didn’t apply. This distinction was confusing to many, and some SEOs felt Google should at least inform sites that they were affected by Penguin. Google did not do this, preferring to keep algorithmic flags opaque.

Critics argued that this lack of feedback made recovery harder and led to paranoia, with some webmasters disavowing links continuously without knowing if they were still flagged or not. Over time, as mentioned, the integration of Penguin into the core algorithm (and the shift to devaluing rather than demoting) resolved much of this – sites would recover as soon as their link profile improved, no need to wait for a “Penguin refresh” or explicit notification.

There were also opposing schools of thought on how aggressively to pursue link removal. One camp advocated a scorched-earth approach: if in doubt, cut it out. They combed through backlink profiles and attempted to remove any link that looked even slightly low-quality, fearing that a single bad apple could spoil the bunch. Another camp advised caution, noting that having some low-quality links is normal and that over-pruning could throw away SEO equity.

They pointed out that even top sites have some weird backlinks (scrapers, etc.), and Google’s algorithms were likely sophisticated enough to ignore those without needing every site to disavow them. This debate essentially came down to trust in Google’s algorithm – the more you trusted Google to know a bad link when it saw one, the less you felt you needed to micromanage your disavow file. Folks with less trust preferred to actively manage everything. Both viewpoints had valid reasoning given the uncertainty in early Penguin days.

From a broader perspective, Penguin sparked conversations about Google’s role in policing the web. The update put webmasters in the position of having to clean up the web (by removing spammy links) to restore their own standings. Some argued that Google was offloading the work of spam fighting onto site owners – after all, it was Google’s algorithm that counted those spam links to begin with.

On the other hand, one could argue that those links never should have been made, and Google was merely enforcing its rules more strictly. This philosophical debate touches on the balance of responsibility: Google maintains that if you build (or allow) bad links to your site, it’s on you to fix it; critics say Google’s immense power forces everyone to adhere to its standards even outside their own site (i.e., who links to you, which you often cannot fully control).

Despite these debates, by and large the SEO community coalesced around the idea that Penguin made the ecosystem better in the long run. It became harder to cheat with impunity, which meant companies investing in legitimate marketing and SEO were less likely to be outranked by a spammy competitor with a link wheel. Opposing viewpoints tended to agree on the end goal (don’t spam) but differed on the methods and edge cases.

To sum up the nuanced view: Penguin’s 2012 debut was a watershed moment that reformed link building practices. Initially met with panic and pain, it forced a reckoning that ultimately benefited those who adapted. There will always be an element of SEO that chases loopholes (and indeed, black-hat forums after Penguin discussed things like building private “buffer” sites to hide link schemes, or using churn-and-burn domains).

But for the mainstream SEO industry, Penguin shifted the focus decisively towards sustainable, audience-focused link strategies. The conversation changed from “How can we trick Google with links?” to “How can we convince real people to link to us?”. And that might be Penguin’s most important legacy: it aligned the interests of SEOs more closely with the interests of users, content creators, and the search engine – making the web a bit less of a “link spam cesspool” and more of a place where earned authority wins.

By

By